Peer-to-peer play

Peer-to-peer (P2P) play involves a traditional server-client arrangement to perform match-making before moving to a P2P style game, where a client machine is connected to by others, and will run the game server code on that one client's machine instead.

After the server gets details from the client about what sort of game session they want, and possibly details about the quality of their connection or their client machine, then the server adds that client to their match-making list. Eventually, it finds a a client to play with them, and decides one should host, and the other connect to them.

A hosting client must be accessible by a shared LAN, by port-forwarding or uPnP router configuration, or by use of firewall hole-punching, so the non-hosting client can access them.

A client hosting a game, rather than all messages passing through a central game server, is the basis of peer-to-peer play, with the main server-side code running outside of the game creator's servers. This has benefits, in latency and server costs, and downsides, in terms of game cheating and needing to write a matchmaking server.

This matchmaking process is manual, it's not part of Lacewing. It can't be, as one Lacewing game could be doing chess, another could be doing MMORPG, and the importance of the hosting client <-> non-hosting client ping in those two styles of game is very different, as is deciding who should play a game with who, as Lacewing has no concept of ranked play.

For people who are new to hosting servers, or just starting their game, P2P is not recommended, as you won't have a player base large enough to make P2P setup worth it. A near-empty server is very unattractive to players; if you have some players, but not many, consider running a Discord server or doing events to pull the small player base together. Whatever the case, marketing is most of the battle: keep your community active and a comfortable environment.

Since Blue Client build 106, Blue Server b40, you can do LAN server searching so players can very easily host their own LAN games. Earlier Blue can host and connect on LAN, but older Blue clients will not be able to scan for servers, and earlier servers will not reply to the scan messages, so the clients will have to know the server's IP address by user input.

Benefits to P2P include:

- Less server machine load.

- The hosting client and non-hosting client may be closer together than they are to the server, decreasing the game latency (reaction time).

- It's not far from allowing players to deliberately host by themselves in a traditional server-client setup, as all the server code must be there. So you can easily make a public server program for your game by re-using the hole punch server-side code.

Downsides to P2P include:

- Not every player has a network that can play P2P; some may be on mobile data and can't host, or are playing a game at work on a lunch break.

- Not every player has a fast enough machine to run server code on top of their client code, and programming Fusion so both Client and Server messages produce the same visual result is big time sink.

- You're left with options of doubling up the server code and client code events so the hosting client doesn't need to get player messages to change its visuals, or having the hosting client connect to itself via localhost to be a player, adding a bit more overhead.

The second is much simpler to program, however. - Match-making is complicated, and there are umpteen factors in choosing a good hosting client; bandwidth, CPU speed, type of hosting, uPnP availability, IPv6 availability, static vs dynamic vs CG-NAT IP, firewalls, etc.

- P2P players can cheat very easily compared to traditional server-client arrangements. Anti-cheat measures will fail if the player deliberately connects to another cheater.

- If a match is aborted mid-way, from either side, is the match-maker server notified about that from the other client? Can the match-maker server be lied to?

- If your game is poorly designed (see Security), an exploited client can take advantage of that.

Normally, clients can't impersonate a server, but in P2P a hosting client acts as a server, so there's more risk.

For example, if any "server", be it match-maker server or a hosting client's server, can tell a client what their new global score is, a malicious hosting client can reset every player's global scores that connects to them in P2P. If any "server" can get the client to send their login details… well, might as well leave your car doors unlocked.

Read the Security topic, and make sure your match-maker server allows clients to report others or block others; and bear in mind malicious clients may produce false reports.

Router configuration

A router must be programmed to forward incoming internet-based connections to their local network device, called port forwarding, which is discussed more in Hosting a server. Otherwise, an incoming connection is denied at the router, and doesn't even reach the server machine.

Traditional server machines come with their routers and server firewalls set to allow all incoming connections, although an application must be hosting to accept the connections. The usual service programs that respond, such as Windows network file sharing, are carefully tuned to only respond to LAN connections… if those services are running on the server at all.

While this router configuration can be done manually, and it's recommended to do a manual set-up if you're hosting a 24/7 server from home (see Hosting a server), the router can also be configured at runtime.

Port forwarding rules can be created at runtime, using IPv4 uPnP technology (such as uPnP Object). uPnP is commonly available in most consumer routers, but often disabled by default for security reasons.

Similar, but much less common technology such as Port Control Protocol exist for IPv6.

Firewall hole punching can be used in scenarios where these methods are not available.

Firewall hole punching

Firewall hole punching does not use uPnP or port forwarding technologies, but instead exploits the fact that outgoing connections are permitted by default in routers, with a firewall exception created as a connection attempt leaves the router's network.

Google can't connect to you uninvited, but you can connect to Google uninvited, because the router sees your outgoing attempt and permits it.

If an incoming connection hits the router close enough to an outgoing connection on the same port tuple, the connection will be allowed despite the lack of port forwarding or explicit firewall rules.

A port tuple is a set of "protocol, remote port, remote IP, local port, local IP". An exact match is needed for hole punch connection to be successful.

The local port is otherwise usually irrelevant for normal connections, which is why multiple websites can be accessed by your web browser despite them all hosting on the HTTPS remote port, 443.

A random local port is generated for an outgoing connection, or one can be selected.

For a hole punch to work requires good timing from both sides, and foreknowledge of what ports are going to be in use on the other side, which requires applications to be designed to set their local ports. So while firewall hole punching may seem like a security risk, applications have to be deliberately designed to permit it, and must foreknow and/or explicitly set their port numbers.

To exchange these port numbers and IP addresses, you need a traditional server, typically considered a match-making server, which will be connected to normally by clients waiting for a game. The server will appoint a hosting client and pair them with non-hosting client(s), swapping IP addresses and ports, so both sides can both hole-punch to each other.

The timing and order of events is important in a hole punch. The recommended process is:

- The hosting client hosts its main port, or is already hosting there.

- The matchmaker server selects a client and a server machine. It picks two port numbers by random number, and exchanges the hosting client IP and port with the non-hosting client, and the non-hosting client IP + port with the hosting client.

The hosting client's main port must differ from its port number chosen by matchmaker.

While you can re-use port numbers, there's a good chance you will have issues with the OS still having the port reserved.

Hereafter, the hosting client will be called "client", the non-hosting will be called "server". - The server performs a hole punch connection to the client on the client's IP + port, punching from the pre-arranged server local port.

- The other side, the client, waits 1 second after step 3. (see note)

- The client sets their local port, then connects to the server machine on their given port.

- Other clients can be connected to the server by hole punch, by repeating steps 2-5 with new ports.

Clients that can directly connect to server, such as LAN clients, can use the server's main port to connect as regular clients.

Note that in step 4, the extra delay on the client connect is necessary. Too short and the connections may miss each other. Too long, and the network devices along the route will remove the connection entry, and the client's connection will fail and timeout.

In tests with one user, a successful connection varied between 0.5 to 7.0 seconds of extra client delay, meaning that step 3 happened at T+0.5 seconds, and step 4 happened at T+1.0 seconds.

Multiple other tests show that around 1.0 second is ideal, and beyond 3.0 seconds you start to encounter more issues.

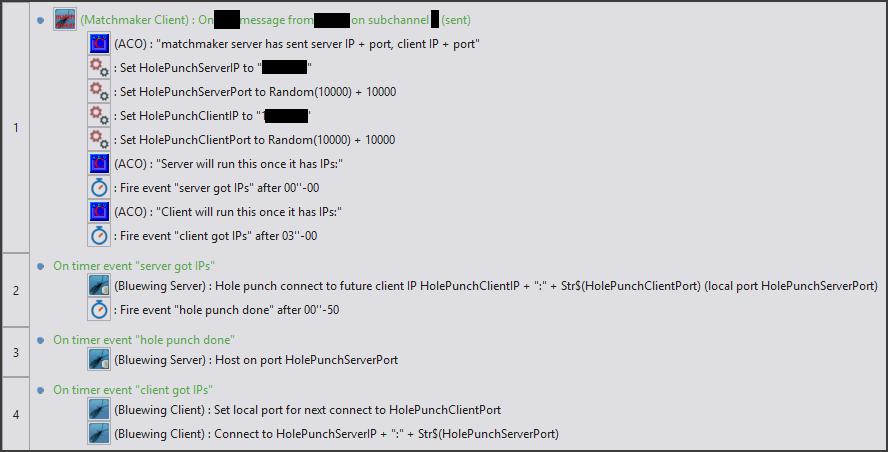

Here is a rough example showing both sides of the process:

Other things not handled in this example:

- IPv6 addresses are [IP]:port, not IP:port. A flat IP + ":" + Str$(port) won't work for IPv6.

- The match-maker server should send which role each side is using.

- Errors are not reported. While some errors can be ignored, others should be noted as signs the player cannot host a P2P game, or that there are mistakes in timing.

- uPnP is usually preferable over hole punching, if available.

- If system time is used to sync the client and servers' relative timings, the system time must be accurate on both sides. You should also bear in mind timezone differences, which can be different in intervals of 15 minutes.

If you are using messages to start the connection process, bear in mind latency differences; the hole punch server side should initiate the process as it's more important they are early. - Some clients are far from the server, but close to each other. The match-maker server should note their timings on connecting to each other should be smaller, and should prefer to connect them together if possible, as they will have a smaller ping.

- Two people can play the same game on the same LAN. The matchmaker shouldn't attempt to P2P connect them to each other, as they are behind the same router. Use LAN server searching on the client instead.

- Two devices may have the same IP but not be on the same LAN; for example, CG-NAT, used in some mobile data networks, will use servers like proxies, and so multiple clients may share an IP.

- And two devices might be on the same LAN but can't see each other due to firewall rules or router configuration; for example, two people in a hotel may be unable to see each other as guests aren't allowed to see each other.

- Conversely, don't always pair players by stats like small latency to each other, or by similar ranking. It'll lead to constantly replaying the same players, which will get annoying. Consider using bots to flesh out games, or spicing up the matches so the same players will have different experiences.

- Some clients have IPv6 addresses alone, or IPv4 alone, due to their ISP routing, or their own router or machine setup. An IPv4-alone client will not be able to connect to an IPv6 address. The reverse may not be true, due to IPv6 supporting mapped IPv4 addresses.

- For privacy reasons, it is normal for IPv6 clients to switch their outgoing connection IP address on a timer, or even create a new IP per outgoing connection. So if you are reading an IPv6 address, you may read a different IP address to the one that will be used for a later outgoing connection, due to IPv6 temporary private addresses (RFC 4941).

If an active connection is using a temporary IPv6 when it expires, then the IP is kept alive for that connection, but is not usable to new connections. Since approx. 2011, temp IPv6 is enabled in OSes by default. - The matchmaker server should keep track of which clients fail to host properly, and try to make them P2P client role only, or relegate them to standard server-client and no P2P.

You should note that some client machines are behind difficult networking arrangements or rigid firewalls, making it impossible for their machine to be on either side of a hole punch.

The match-maker server should account for these failures, and should also note clients with large ping delays, slow machines or frame drops.

While it is academically possible to hole-punch connect two client objects or two server objects to each other, the Bluewing Client expects a Server format of response, and vice versa, so the connections will be terminated quickly.

Bluewing Server build 39 introduced single-client P2P, where the server's main port is used for a single hole punch client, suitable for 2-player games only.

Bluewing Server build 40 expanded to multi-client P2P, giving hole punch clients their own port each on server side. Any hole-punch clients must connect to a different port to the main Server port.